8. Then Poemander said to me, Do you understand this vision and what it means? I shall know, said I. Then said he, I am that light, the mind, thy God,1 who am before that moist nature which appeared out of darkness; and that bright and shining word from the mind is the Son of God.2

1Hermes corroborates the conflation between mind and God, and emphasizes the nature of that God not only being mental but also light, which would be echoed millennia later by Walter Russell’s conception of divine light, wherein unmanifest God is undifferentiated light and manifestation is differentiated light, which would be similar to conceptions as to how the aether operates as a medium for manifestation.

2Calling the word from the mind the son of God is wholly accurate and poetically so. This means to say that the word is the imagined image, and the mind is the imaginer who imagines the image, thus fathering the image, making such an image a son of God, mind.

9. How is that I asked? Thus, he replied, understand it: That which in you sees and hears the word of the lord, and the mind the Father, God, differ not one from the other; and the union of these is Life.3 I said, I thank thee. He said, but first conceive well the light in your mind, and know it.4

3Knowing the word is the image of the imagination, and thereby corresponding with all manifest reality as we experience it, what else but consciousness sees and hears and elsewise experiences the word of the lord? Of course this refers to consciousness, and Hermes is clear in saying that consciousness and mind, God, are one in the same, he says these two in union is the cause of life. Union being the default state of sameness implies life is inevitable, an attribute of God.

4Knowing light is God, or perhaps more specifically the substance of manifestation, to know this light within oneself could have several implications. Perhaps identifying oneself with the universal one substance of manifestation, or rather given the preceding context of recognizing God in oneself it rather refers to one’s power over light given the command to conceive the light in the mind.

12. … But how, I said, or from what substance are the elements of nature made? He said, Of the will and counsel of God; which taking the word, and beholding the beautiful world imitated it, and so made this world, by the principles and vital seeds or soul-like productions of itself.5

5Hermes first clarifies that the substance of manifest reality is ultimately the will of God. The beholding of the image of the world seems to refer to the process of imagination: God takes the word, which we understand to mean the image of the imagination, and with it beholds the world, which is to say the world is the image and therefore it is made manifest, or is imitated. So the world is made, and given the nature of its manifestation being the image of the imaginer, mind, it is of mind and thereby imbued with the vital seeds of that mind.

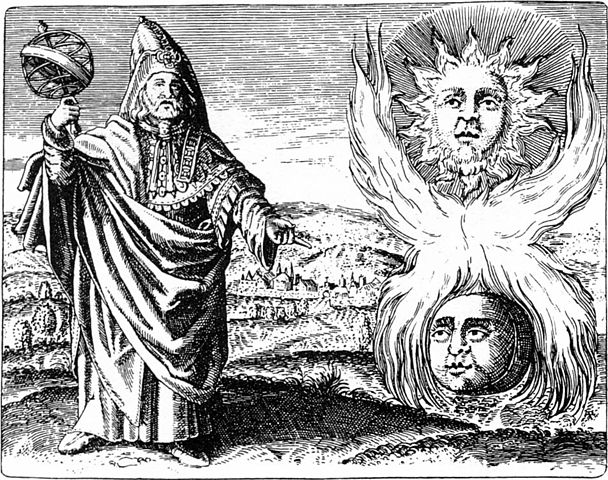

13. For the mind being God, male and female, life and light,6 brought forth by his word another mind or workman; which being God of the fire, and the spirit, fashioned and formed seven other governors, which in their circles contain the tangible world, whose government or disposition is called fate or destiny.7

6Here Hermes alludes to the polar, not dual, nature of mind and God. Male corresponding to the inhalation of mind, the charge, contraction, gravitation, and life, think your inhalation of breath giving you life, and female corresponding to the exhalation of mind, the discharge, expansion, radiation, and light.

7This passage is important for two reasons. First, Hermes seems to reference a demiurgic and following archontic natures rather forthrightly, though it should be noted that if this is so the perspectivxe varies from that of the Gnostics, given that this Hermetic interpretation clearly defines both the Demiurge and his Archons as wholly of God, and in fact an intentional creation of God and wholly reflecting God. The second reason for this passage’s importance is that it affords us an opportunity to speak on self-referentiality, or correspondence between God and his creation. For instance, the referenced created mind or Demiurge is referred to as a mind and workman just as is God, and of course, a Demiurge does as God does, making manifest, even in the passage this created mind brings about seven more governors to contain the material world. The key takeaway in this is to see the “layers” of reality imitating and referencing one another, which is the primary point of self-referentiality in layman’s terms. This occurs due to God’s immanence in all of his manifestations, as such they will all mimic God’s nature as they are wholly permeated by God.

14. It straightway came forth, or exalted itself from the downward elements of God, The word of God, into the clean and pure workmanship of nature, and was united to the workman, mind, for it was con-substantial;9 and so the downward born elements of nature were left without reason, that they might be the only matter.

9Here it is said that the word, which is the image and workmanship, and the mind, which is the imaginer and workman, are consubstantial, that is to say one is indistinct from the other, or more accurately that the imaginer cannot be severed from the image and vice versa. This lack of privation is extremely important and applicable on a broader scale in monism.

Discover more from BREAKING NOUS

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Leave a comment