As we all know well, Pythagoras and those in his tradition that followed, ground their metaphysics in number and had a well developed system of numerology, within the context of which each number is a particular system unto itself, each reflecting to various meanings relevant to the number in question. For example, the Dyad, a system of twoness, extends its meaning to indefiniteness, unlimitedness, ration in proportion, matter, gender and so on.

Before continuing its worth noting that the Pythagoreans held that one, the Monad, was prior to number, as the unit of number, and that all numbers were indeed numbers because they were enumerations of one, the unit.

Many of you reading will be very familiar with The One (in Greek: To Hen) of Neoplatonism, and its priority over both the Monad and the Indefinite Dyad. In Pythagoreanism however, it seems like the Monad as the Limit itself is the Primary Principle and the unity from which all things arise, and of which the Dyad is an enumeration, whereas in Neoplatonism, The One ineffably prepossesses both principles.

With the Monad and the Dyad in mind, oneness and twoness, and the Limit and Unlimited respectively (In Greek, Peras and Apeiron), the Pythagoreans formed a table of opposites, which will help define the first two numerological systems and their dynamic.

The pairs follow as:

Limit and Unlimited, the Monad is considered the Limit because it is unitary, whole and indivisible, limit is considered positively, as though it is definite reality. The Dyad is the unlimited because it is inherently dual-aspect, meaning it has inherent opposition and plurality, lacking principle unity, and it is of course divisible.

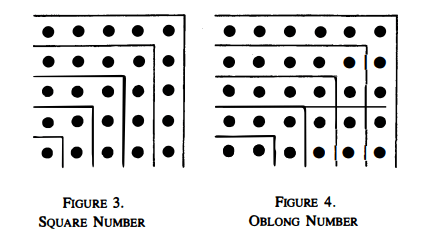

Odd and Even, the Monad is associated with the odd not only because 1 is an odd number, though again 1 isn’t considered a number by the Pythagoreans, but also because odd numbers cannot be evenly divided whereas even numbers can by divided right down the middle. We’ll see further elaboration of this with Square and Oblong shortly.

Unity and Plurality, this one is fairly straightforward, the Monad is unity, and the Dyad is the initial advent of plurality in the enumeration of the Monad. A bit tangential but I can’t help but be reminded of Leibniz’ Monadology, wherein plural monads are essentially enumerations of the Monad – though his position is generally mistaken as metaphysical pluralism because of this.

Right and Left, this pair probably alludes to the right and left hand paths, which I would describe as relevant due to the right hand path being preponderantly reversive in nature, and reversion is aimed at attaining greater degrees of simplicity and therefore unity, as opposed to the processiveness of the left hand path which is generally associated with complexity, totality, bearing in mind that a total is composite, and plurality.

Male and Female, gender is always an interesting thing to see in metaphysics, and of course it makes sense for it to have a place therein. The masculine principle is regarded as the definite, concrete and primary principle, whereas the feminine principle is regarded as indefinite and posterior. Remember that the Dyad is the first instantiation of plurality, and that the indefinite is taken as necessary for the continued succession of enumeration. This is to say that it is essentially the principle of gender, and is responsible for birthing the continued succession with the input of units, bearing in mind again that each successive enumeration is indeed an enumeration of the unit itself. This does perhaps make more sense if there is a principle prior to the Monad, in which the limit and unlimited both exist in a predivided and prepossessed manner, as we see with the One of Neoplatonism.

Rest and Motion, rest is associated with the Monad again because it is complete in itself, taken in itself there is no exteriority to which it can move on account of its absoluteness, the Dyad is taken to be motion as it invites dynamism between two, whereas without it there is only oneness. To my mind this would have to be situated carefully in metaphysics, as on the surface it seems to contradict what we have just predicated of the Monad, in that it would seem to preclude the existence of the Dyad. I would go so far as to argue that the enumeration of the unit occurs virtually within itself, meaning the capacity for such a virtualization or imagination would have to be prepossessed by the Primary Reality Principle, but I imagine I’ll make another work entirely devoted to that topic.

Straight and Crooked, this one is a little more abstract and symbolic, as you should avoid thinking of a straight line in the literal, infinitely divisible sense, but rather understand it here as getting to the straightness in itself representing uniformity in distribution, whereas the crooked line invites deviation and the succession of lines into planes, then solid figures, then sensible bodies.

Light and Darkness, the Monad as light because light is substantial in itself, whereas darkness is a privation of light, such a privation being necessary for distinction from pure light as the succession of numbers is applied to the definition, particularity and plurality of the manifested, engendered world.

Good and Bad, similar to the previous pair, Goodness is concieved chiefly as that which is primarily, badness or evil as privatory in nature, lacking any substantial existence in itself, rather existing purely in the context of what is.

Square and Oblong, this one is interesting, the pictured diagram will be helpful for understanding precisely what is meant. The idea is that if you start with the unity, drawn a right angle around it, then add 3 units around those lines, and continue to do this with odd numbers, the shape you will get indefinitely is a square that is always even on both sides. Whereas when you start with 2 units, then commit to the same process with each even number, the sides are always of unequal length. The Dyad is therefore demonstrated to be associated with oblongness, difference and inequal distribution, whereas the Monad is demonstrated to be associated with squareness, sameness and equal distribution.

With that we have the Pythagorean table of opposites.

To apologize for the Pythagorean Monads primacy, I will say that it was conceived of in a way as both even and odd, remembering that the unit was not held to be a number itself, rather the object of enumeration, and therefore that odd numbers participate in the unit more than the even numbers do, which can be considered as odd numbers symbolically being a more immediate mimesis of the unit. This understanding of the Monad seems to lend itself more appropriately to what is demanded of a primary principle, similar to the Neoplatonic One, that the conception I previously relayed. A relevant quote from Theon of Smyrna’s Arithmetic Fragment 199B reads:

“The unit partakes of the nature of both, since when added to an even number it makes it odd, and when added to an odd number it makes it even; hence the unit is called even-odd.”

Arithmetic, Fragment 199R, Theon of Smyrna

This Nousletter will also be formatted as a video on the Ars Philosophica YouTube channel.

Discover more from BREAKING NOUS

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Leave a comment